Everyone’s talking about MCP (Model Context Protocol) and how it’s supercharging workflows in tools like Claude Desktop, Cursor, and other desktop apps. And yeah, the integrations with desktop environments are cool. But honestly, MCP is way more than just these integrations for desktop applications.

You’ve probably seen folks compare MCP to USB-C for AI. It’s a “not so bad” analogy, especially for explaining the concept to non-technical folks. But if you’re an engineer, that metaphor doesn’t quite capture why this is actually a big deal.

So in this post, I want to go a bit deeper from the perspective of an engineer. Let’s look at why MCP could be a game-changer for us, especially if you’re building Agentic AI Applications.

Understanding LLMs: Text In, Text Out

Large Language Models (LLMs) are indeed text generation engines. I shared this in the previous post about The Turning Point in AI.

By default, they (LLMs) are stateless and non-interactive. You provide an input prompt, and they return a text output. This setup works well for text generation tasks. For example, asking a question or generating a poem.

But let’s say you want the LLM to actually book an appointment for you. Well, it can’t. Not out of the box.

That’s because LLMs are built to understand and generate text. They’re not built to take real actions in the world. They can’t call an API, talk to your calendar, or click a button on your behalf.

So if you ask, “Book me an appointment next Tuesday at 3 PM”, it might say, “Sure, done!” But nothing’s actually happened. It didn’t reserve anything on your calendar. It just gave you a nice-looking answer.

To be fair, it can still help. It might suggest available times, walk you through the steps, or even draft an email to your assistant. But unless you connect it to the right tools and systems, that’s where it ends: text, not action.

Before MCP: Function Calling

LLMs were great at generating text responses, but they couldn’t actually do anything. So, engineers came up with “Function Calling”, a way for the model to say, “Hey, I think we need to run this specific function to get the job done”.

Instead of just giving back a paragraph of text, the LLM can now generate something like check_availability("2024-06-10", "15:00"). That suggestion can then be picked up by the system, executed in your backend, and the result sent back to the LLM to continue the task.

It’s not perfect, but it was the first real bridge between language models and the outside world.

For example, consider a simple example, building an appointment booking assistant:

First, the LLM is prompted with the prompt below.

You are a helpful assistant who can call external functions to help users book appointments.

Available Functions:

1. check_availability(date, time): Checks if the requested date and time are available.

2. reserve_slot(date, time, user_info): Books the appointment if the slot is available.

3. send_confirmation(email, appointment_details): Sends a confirmation email to the user with the appointment details.

4. get_available_slots(date): Returns a list of open times on the given date.

Your task is to determine what information is needed and in what order to complete the booking. You need to generate the appropriate function calls and return them to me in a JSON structure. I will execute the calls and return the results for you to use in the next step.

Example:

If the user requests an appointment on June 10th at 3:00 PM, and their name is Alex with the email alex@example.com, you need to generate function calls like:

[

"check_availability(\"2024-06-10\", \"15:00\")",

"reserve_slot(\"2024-06-10\", \"15:00\", {name: 'Alex'})",

"send_confirmation(\"alex@example.com\", {date: '2024-06-10', time: '15:00'})"

]Then, the LLM identifies the necessary steps: checking the time slot, reserving it, and sending confirmation.

[

"check_availability(\"2024-06-10\", \"15:00\")",

"reserve_slot(\"2024-06-10\", \"15:00\", {name: 'Alex'})",

"send_confirmation(\"alex@example.com\", {date: '2024-06-10', time: '15:00'})"

]When the model outputs something like the above response, it’s up to your system to take that and do something real with it.

That means you need a function handler on your end. Something that listens for these function call suggestions, executes the actual logic, like calling an API or querying a database, and then feeds the result back to the model so it can keep going.

It’s like having the LLM drive the conversation, but your backend does all the hands-on work.

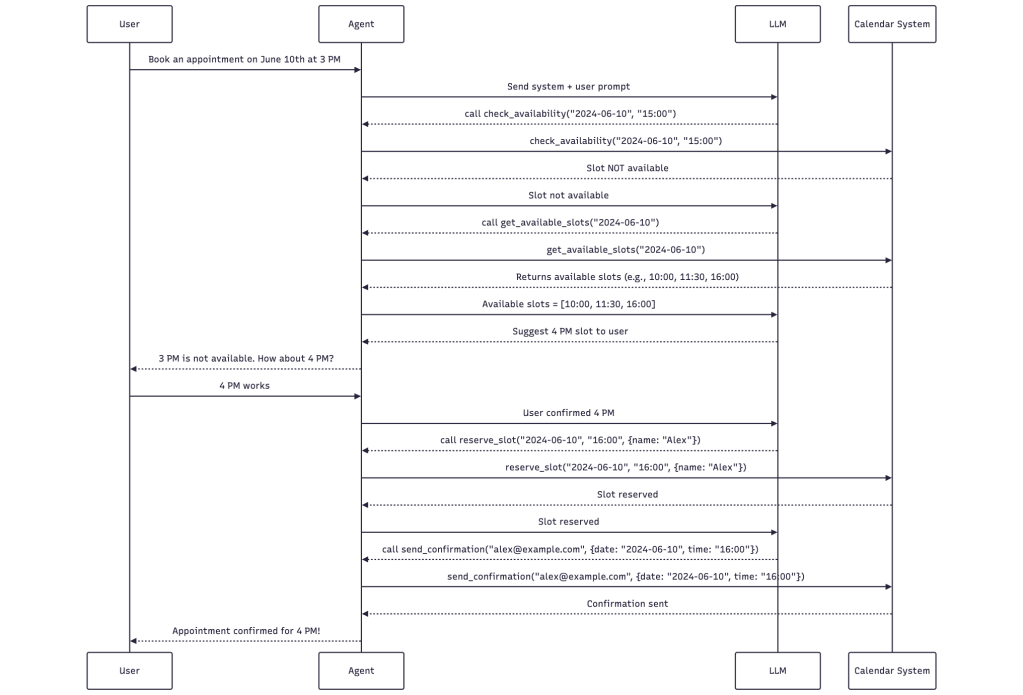

The sequence will look like:

- The LLM suggests calling

check_availability("2024-06-10", "15:00"). - The agent runs the function and receives a response: not available.

- The LLM is notified and suggests calling

get_available_slots("2024-06-10"). - The agent fetches and returns available slots:

["10:00", "11:30", "16:00"]. - The LLM reasons and suggests offering “4 PM” to the user.

- The agent asks: “3 PM is not available. How about 4 PM?”

- The user replies: “4 PM works”

- The agent confirms with LLM.

- LLM suggests calling

reserve_slot("2024-06-10", "16:00", {name: "Alex"}) - After successful booking, the LLM requests:

send_confirmation("alex@example.com", {date: "2024-06-10", time: "16:00"}) - The agent executes and confirms back to the user.

This demonstrates how LLM and Agent cooperate using a structured, multi-step tool use. Each step is handled with hardcoding inside the agent.

Here is a simple diagram to describe the flow:

The Scaling Challenge

As we build more capable AI systems, we naturally want them to connect with a growing number of external tools, such as APIs, services, databases, etc. But each new connection adds complexity.

Every time we want the LLM to work with a new service, we have to:

- Define a function that the model understands

- Write backend code to handle that function call

- Manage how it talks to the API and how we handle errors

- Keep track of changes if the API evolves

And the more tools you plug in, the more of these little pieces you’re juggling. It’s like duct-taping together a growing tower of adapters. It works, until it doesn’t.

Here are some key problems when the system is growing:

- Too Much Maintenance: Every function you add is another thing to look after. If an API changes, you might need to update several parts of your system just to keep things working.

- Scaling Problem: As the number of tools and services grows, so does the number of functions, and keeping track of all of them becomes a full-time job. Finding what function does what, or figuring out if something already exists, turns into detective work.

- No Standard Format: One LLM might want function definitions one way, another wants something totally different. So a function that works great in one setup might be useless in another.

- Inconsistent Error Handling: Everyone handles errors their own way. Some people forget to do it at all. Others copy and paste from another file. The result? Bugs that are hard to trace and even harder to fix.

- Security Risks: Whenever you hook into an external system, you’re responsible for doing it safely. That means dealing with auth, handling sensitive data, and protecting against misuse, and all of them get harder the more integrations you have.

But there’s a deeper challenge. It’s not just about how many functions you have. It’s about how they work together to actually get something done.

Most real-world tasks don’t end after one API call. They’re messy, conditional, and multi-step. You rarely just “check something” or “submit something” once and move on. Instead, you’re doing a mix:

- Ask for available appointment slots

- Suggest one to the user

- If the user declines, ask again

- Once they agree, reserve it

- Then send confirmation

Every step relies on the result of the previous one. And you need to handle all the little details: what if the slot is taken before you reserve it? What if the email fails to send? What if the user changes their mind mid-process?

Trying to hardcode that logic for every use case gets out of hand fast. You end up with scattered workflows, spaghetti conditions, and way too many edge cases.

We need something better, something that doesn’t just define what a tool can do, but helps us structure how multiple tools can work together smoothly. That’s where abstraction and better orchestration come in.

Introducing MCP: Standardizing Interactions

Model Context Protocol (MCP) was created to solve a growing problem: as function calls in LLM apps grew, they became harder to maintain, scale, and standardize.

This kind of problem about managing complexity and avoiding repetitive code is not new in software engineering. A common solution is to introduce a layer of abstraction. This lets developers handle common tasks in a consistent way without rewriting logic every time.

Take database access as a real-world example. In a typical backend system, instead of writing the raw SQL queries everywhere, we use an abstraction like an ORM (Object-Relational Mapping). It standardizes how we fetch, insert, and update records. Developers just define models and use high-level methods, then everything else is handled under the hood.

This means:

- You write less boilerplate code

- The system is easier to maintain

- Different parts of the codebase can reuse the same logic

MCP is doing something very similar. It’s an abstraction layer for how LLMs interact with external tools.

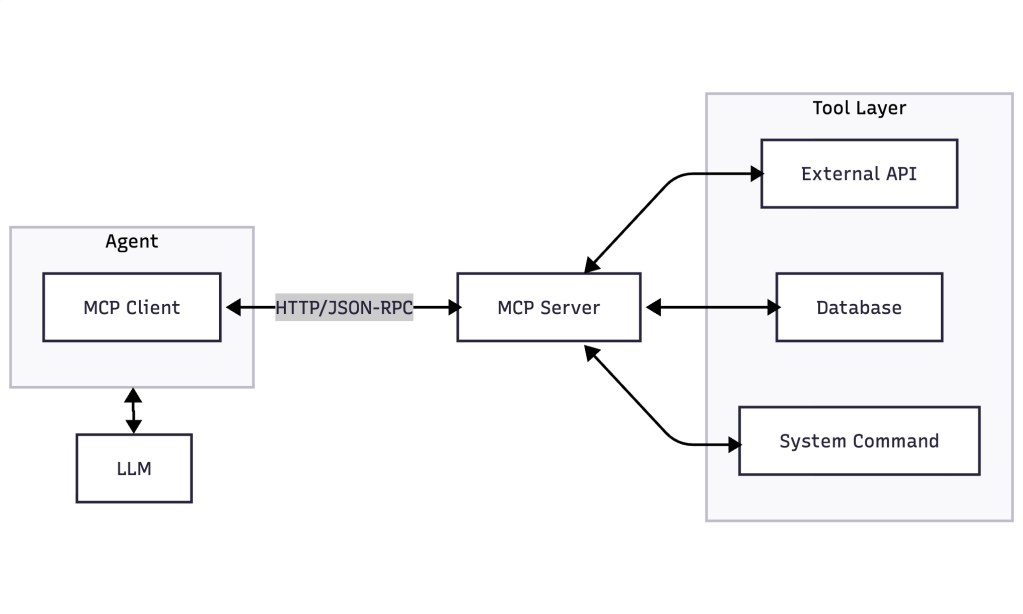

MCP is built on a simple client-server model.

- MCP Clients are LLM-powered apps that need to use external tools.

- MCP Servers expose those tools, things like APIs, data sources, or even internal services.

The two sides talk using a shared protocol. Communication can happen over stdio, HTTP, or RPC. That flexibility makes it easy to plug into different environments, whether you’re building something lightweight on the desktop or deploying at scale in the cloud. We might dive deeper into the MCP architecture in another post. But it brings several benefits:

- Standardization: MCP defines a clear format for how tools are described, how requests are made, and how responses are handled. By setting up a standard contract between the client (the LLM app) and the server (where the tools live), it makes integration more predictable and easier to manage.

- Maintainability: When everyone follows the same interface, updates become less risky. If one team updates the MCP client or another modifies the MCP server, things won’t break as long as they stick to the protocol. Tool providers can improve their servers independently, and client apps don’t need to change right away.

- Scalability: MCP is built to grow. For example:

- Tool Discovery at Runtime: Tools can be listed and described in a standard way, so apps can discover what’s available without hardcoding. Clients can ask, “What tools do you have?” and get back a list they can use right away.

- Decoupling: The apps (clients) and the services they use (servers) can run separately. You can scale or update each part independently based on usage. You can add new tools, move them to another machine, or update existing ones, all without breaking the rest of your system.

Instead of writing all the logic for calling, managing, and coordinating tools in the LLM app, MCP moves that complexity to the server side. Developers can build and maintain powerful, reusable MCP servers. Then, any LLM apps that use MCP can plug and play with far less effort.

For MCP to really take off, it needs widespread use. Being open-source is an advantage. The value of any standard depends on the number of people who use it. If lots of tools are available via MCP, more LLM apps will support it. That will encourage even more tools to adopt MCP. This creates a network effect.

MCP in Agentic AI Development

MCP (Model Context Protocol) is a game-changer for building AI agents that can take actions and use external tools. Instead of being stuck inside desktop apps, agents with MCP clients can work independently on any machine or in the cloud.

Think of an AI agent with two parts:

- One part does the thinking (reasoning, planning, deciding)

- The other part uses tools (fetches data, calls APIs, interacts with systems)

MCP makes it easy to split these two parts. The agent doesn’t need to know how every tool works. It just sends requests to an MCP server, which handles the rest.

Let’s go back to the booking assistant example. Before MCP, if you wanted to build an appointment booking agent, you had to code every detail by hand:

- How to check availability with the calendar system

- How to structure each function:

check_availability,reserve_slot,send_confirmation, etc. - How to handle edge cases and errors if something fails mid-process

With MCP:

- You just point the agent to a “Scheduling MCP Server”

- That server exposes standardized tools like

check_availability(date, time)andreserve_slot(...) - The agent can discover and call those tools as needed, removing the need to wire the logic into your app

Now the agent’s logic is focused purely on reasoning and dialogue, while the server takes care of all the operations. They can even run separately: your agent could live in a lightweight web app, and the MCP server could sit in the cloud, serving multiple agents.

It’s clean. It’s scalable. And it means you can build smarter, more modular systems without getting buried in orchestration logic.

Conclusion

MCP isn’t just another tooling, it’s becoming the “infrastructure” for building AI agents that can actually do things. It gives LLMs a standard way to access tools, perform real-world actions, and participate in workflows, not just generate text.

Of course, MCP doesn’t magically fix everything. It doesn’t magically fix unreliable APIs or bad system design. But it gives us a clean, consistent interface to work with, and that’s a big deal. It opens up a more flexible, distributed way to deploy and scale agent applications across different environments.

For engineers building the next wave of AI apps or AI agents, this is where things are headed. The ecosystem’s still young, and the best practices are still being written.

That’s what makes it exciting.

Discover more from Codeaholicguy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This was a thoughtful deep dive into why MCP matters for engineers, especially the way it connects different components and workflows in modern systems. As I’ve been exploring how MCP server implementation and deployment work in practice, I found this resource here: https://mobisoftinfotech.com/services/mcp-server-development-consultation which added some helpful context around development and consultation. Thanks for sharing your insights — it definitely gives a clearer picture of the technology’s importance.